Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction by Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner

I wanted to review this with War and Peace, as many parts of this book are a scientific explanation of Tolstoy’s ideas. Thanks to the friend who recommended this.

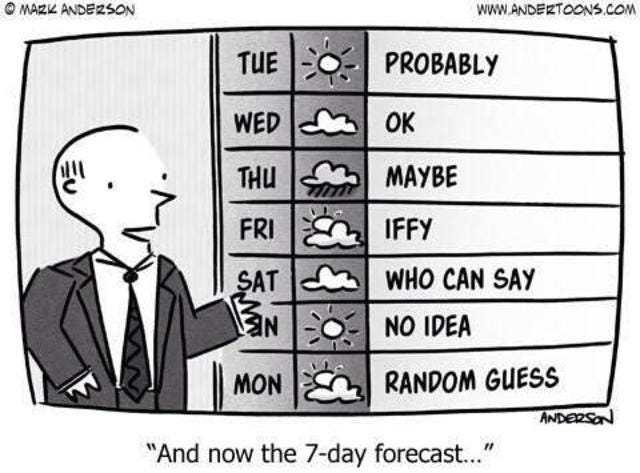

Many forecasters and pundits are wrong.They make vague predictions ("there will be a change in the future"), don't check their own accuracy, and are overconfident. Indeed, the reasons why they are pundits is because they are over-confident: who wants to listen to someone hem and haw? We want certainty and entertainment. As consumers of forecasts, we don't demand ones that are high quality. Instead, we crave “hot takes,” reassuring ideas, and neat theory we can deploy at cocktail parties.

This idea reminded me of Tolstoy's writings on the impossibility of truly understanding history: how we will arrange historical data to "prove" we are right, and ignore our false predictions.

Tetlock and Gardner cover this and more in Superforecasting. The inspiration for the book was the Good Judgment Project, an online forecasting contest which anyone can enter (sample question: "Will Bashar al-Assad cease to be president of Syria before 1 January 2019?") The authors studied successful forecasters - "superforecasters" and drew out some lessons on how to better forecast.

So, how do you forecast well? There are a few things you can do:

Be open-minded. Check information that is contrary to what you want to believe. In other words, be vigilant in avoiding confirmation bias.

Break down large questions into small questions. (e.g., will Donald Trump be president in 2022 = Will he run in 2020? If so, will he win? If he wins, how likely is he to still be in office in 2022?).

Use objective, “outside-in” thinking. What is the % chance something will happen, based on historical data? For example, if I'm trying to estimate how likely I am to have a job post-graduation, I might assume a 0% or 100% chance, based on how I feel. But, I can check objective data and see that 80% of people at my school do have jobs post-school). I can then use this as a baseline.

Be in perpetual beta. Focus on self improvement and updating your beliefs / information. A forecast is never “done.”

Better to know a small amount about many things than a lot about one thing. Or, in other words, be a consumer of many different worldviews and analytical tools, as opposed to viewing everything through one grand theory / Big Idea (e.g., free markets, globalization, etc).

Update your beliefs constantly in the face of new information.

Think in precise probabilities. Is something 50% likely to happen, or 51%. This helps you think more accurately and better refine your assumptions.

A few other points / questions:

It's impossible to evaluate forecasts in the short-term. Let's say the weatherman says there is a 60% chance it will rain...and it doesn't. This doesn't mean he's wrong, per se. It means that on a day like this, it will rain only 60 out of 100 times. To assess his performance, we'd have to track him over the long term. Over the course of his career, what % of the time does it rain on his 60% days?

Many things are unknowable. A 5-year forecast is likely to be BS. If you believe this, than how do you think about 5 year plans?

I loved the point around how forecasts are generally not evaluated. Take industry forecasts (e.g., estimating how fast a market is growing): companies spend tens of billions of dollars on them a year, but don't typically go back and see if they were right / accurate.

In my opinion, we often forecast for reasons other than predicting the future. We might want to build confidence or examine risks, or understand how something truly works (e.g., if you are build a forecast for a company’s revenues, you will develop a deeper understand of its business model). This isn’t bad, in and of itself, but we should be more explicit about why we are forecasting.

The point about 20/20 hindsight resonated with me. In business school and our culture in general, we venerate "visionaries" who've started wildly successful companies. We always hear about their vision, how they knew this industry was going to change, etc. How much of that is after-the-fact rationalization? Some, I imagine. But when you're in business school or the Valley and hearing all of this, you feel pressure to find "the next big thing" or "get in at the ground floor somewhere,” even though the people saying that didn’t necessarily do so themselves.

One great irony is that the smarter you are, the better you get at self-rationalizing and ignoring your biases. (Heard this from Shane Parrish at the Farnam Street blog)

One thing I grapple with is how to approach confidence in this framework, especially if you work in an industry that rewards confidence and table-banging over thoughtfulness and self-questioning. If you are trying to persuade your firm to invest in a certain business, your colleagues will likely see your confidence as a proxy for the quality of the deal. But, this state of mind can lead to folks ignoring obvious risks and intentionally ignoring information that contradicts their thesis. So, how do you operate in this kind of environment? A few thoughts:

One would be to frame risks as "if you believe X, than it's a good deal," and simply say that you received new information around X.

You can model humility and thoughtfulness around junior team members

You can keep a log of every deal you've looked at (or the analog in your field) and use that to assess your performance (not my idea, brought up by same friend who recommended it)

You can be self-questioning before you present externally. And you can reframe confidence from “I’m right” to “I’ve done my best to verify this is right, and am confident in my process.”

At the same time, though, confidence is obviously an important skill.

I enjoyed this and read it over a long weekend. We live in a world that rewards glib confidence and simplistic answers, so his willingness to challenge that was refreshing. After having read this, I probably spend a bit less time reading about the future (and reading pundits) and more thinking about the present and how to maximize that. Many people business school, have spent a ton of time and mental bandwidth trying to find the perfect post-MBA job. But when you think about it, it's hard to anticipate what a job will look like 10 years in the future. It’s like predicting the weather on May 19, 2027.